|

Back to On the Road with John Tarleton

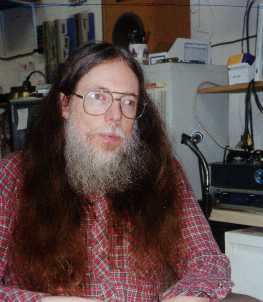

Interview with Stephen Dunifer, Microradio Pioneer

By John Tarleton

BERKELEY, California—Stephen Dunifer is the founder of Free Radio

Berkeley and International Radio Action Training Education (IRATE).

Disenchanted with the direction of mainstream media, he launched his own

unauthorized FM radio station from the hills outside of Berkeley in the

spring of 1993. His transmitter was about the size of a brick.

Free Radio Berkeley came to have 100 volunteers and 24 hours a day of programming. Dunifer would become embroiled in a running legal battle with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) over his right to be on the air without a government license. Free Radio Berkeley was silenced in June 1998 by court injunction, though the case is presently being reviewed by a federal appeals court. Dunifer continues focusing his energy on helping to build a movement; offering workshops and technical support and distributing simple, inexpensive radio equipment (see picture below of 40-watt transmitter) to community radio activists throughout the United States and to places like Haiti, Chiapas, El Salvador and East Timor. An activist since the Vietnam War era, the 48 year-old Dunifer has become the Johnny Appleseed of the Free Radio Movement. "It's important," he says, "to take back the means of communication and put it in as many hands as possible." The concentration of ownership in the radio industry has greatly accelerated since the Telecommunications Act of 1996 was passed with strong bipartisan support. A single owner can now control as many as eight stations in one city. Communities are recast as markets. Identical formats. Automated playlists. Increasing homogenization equals increasing profits. According to the latest data, three companies - Clear Channel (512), AMFM (443) and Cumulus Media (231)- now control almost 1,200 stations. In this cultural wasteland, hundreds of unauthorized, low-power "pirate" stations have taken to the air. Facing a growing movement of electronic civil disobedience, the FCC reversed itself in January and announced it would license 1,000 LP (low-power)-FM stations (ranging from 10 to 100 watts) in the next couple of years. The National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) was outraged. 98% of the radio airwaves are controlled by private commercial stations. And though few of the proposed new low-power licenses would be granted in populous urban areas, the NAB has mounted a furious lobbying campaign on Capitol Hill to have the new FCC regulations overturned. Interestingly enough, the NAB will be holding its annual radio convention in San Francisco from September 20-23. Dunifer and others are planning a raucous greeting for when the NAB comes to town.

Near day's end, people began dividing into committees and passing around sign-up sheets for various listservs. A web site was already under construction. The group gave itself a name—the Microradio Action Coalition (MAC). A certain tingle was in the air. There was the strange and exciting feeling of being present at the conception of another one of these mass, Seattle-style direct actions. The following day I caught up with Dunifer at Free Radio Berkeley's headquarters in a cramped warehouse studio nd he reflected on the past, present and future of microradio.

"A Need That Had to Be Dealt With"JT: We live in a media-saturated society. There's a tremendous number of media outlets including NPR stations in almost every American city. Why is microradio important? SD: It's important for a number of reasons. One has to consider what NPR really stands for. In my opinion, NPR stands for "Nothing to Provoke Rebellion'' or "No Problems Radio". People have very little access as a community to the NPR stations, particularly large flagship stations like the ones we have here in San Francisco. Smaller communities might have a little bit more of a possibility. Even though a person may have access, it doesn't mean they have a voice. The real difference is that micro-powered broadcasting gives communities a voice and allows them to empower themselves with that voice. The real bottom line in this is it allows people to speak to each other in communities, to express themselves, to share their art, their music, their culture, all the rich diversity they have to offer each other. JT: What motivated you to become as involved as you have? SD: Besides sheer obstinacy and bullheadedness, I basically saw a need that had to be dealt with as I was looking at things as they were developing in the early part of the '90s with the Gulf War and local and regional issues and that none of these were being covered. In the case of the Gulf War, you had the military inviting the media into a spare room in the Pentagon and giving forth an arcade game version of the war (then) going all the way down to the bombing of Judi Beri and Darryl Cherney and local issues we were dealing with here in Berkeley over free speech rights, rights of assembly. Issues all across the board were not being represented at all. And if they were, it was very distorted and one-sided. Also, our supposed People's Voice, KPFA, was showing a severe lurch to the center. It all pointed to the fact that we had to look at alternatives how to reach people, how to give them a voice. I had been involved in publishing other things. I didn't think publishing a new newspaper was really going to solve it. Having a background as an electronics design engineer/computer systems person and having a background also as a broadcast engineer, I said, "let's go for it." and look at doing some low power, knowing of some of the efforts of people before like Mbanna Kantako in Springfield, Illinois in the late '80s. I met with people from the National Lawyers Guild Committee on Democratic Communications who had already been working on this issue in relation to Mbanna's situation. They had already done a sample brief that could be used by him or anyone else. The constitutional issues that were raised seemed very creditable to me. The FCC's regulatory policies and structure were overly restrictive because they prohibited stations with less than 100 watts of power. The rules and the process were for people that could afford to go through a $100,000 plus process to get a license. So, Free Radio Berkeley went on the air April 11, 1993 as a free speech voice. It was a protest against the FCC's regulatory policies and a way of providing a voice for the community.

A Campaign of Electronic Civil DisobedienceJT: How has the FCC treated you and Free Radio Berkeley over the years? And, what's your rationale for breaking the law? When is it a good thing to go ahead and break the rules? SD: First off, we have a quote on our web site from Howard Zinn that says, "Breaking the law isn't antithetical to democracy. It's essential to democracy." If people hadn't broken and defied the segregation laws in the South, if people hadn't taken the actions they did during the 1930s labor movements or in the 1890s in the general strike or any number of events and actions that have shaped the history of this country, we would be in a whole different situation. We would be in a Fascist dictatorship if people had not challenged the status quo. This is what democracy is all about. Democracy takes many forms. To me, what we embarked on was a campaign of electronic civil disobedience. We felt the laws were unconstitutional. They were unjust. They violated our constitutional rights (and) our human rights as defined by UN accords. We felt taking action was necessary to force a change in those laws. And in fact, that's what has happened. The FCC was saying three or four years ago in open court documents that they would never visit this issue again. And now, as a form of damage control, the FCC has given us a few crumbs off the table with the new LP-FM service. It's been an interesting relationship for these seven years. They have stalled and stonewalled and prevaricated along this whole issue. So far, they have managed to dodge the bullet of constitutional scrutiny on their whole regulatory structure, which I feel is still unconstitutional. I don't feel they have the right to sell the airwaves in auctions. JT: You say you don't recognize the constitutionality of the way the FCC distributes licenses for radio stations. Sketch out your vision for what would be the optimal setup for distributing what is ultimately a limited, finite resource. SD: There's various ways of looking at it. If we could get 50% of the corporations off the airwaves, that's one way. The other way is to transition in where they give us new spectrum space. For example, open up the FM band at the low end by moving TV channel 6 to the UHF digital, which is supposed to happen. That would open up 30 new channels of FM frequencies. And over a three or four year period, radio receivers could be manufactured to meet that new band requirement. That's not a big issue in my opinion. Already, such receivers exist in Japan because in Japan FM goes down to 78 Megahertz. So, that's the more viable way. They have sort of recognized that. One of our proposals we put to the FCC was to open up that band. Well, now they want to open it up for the new digital broadcasting instead of what we proposed. We know it's a viable option to open up that six megahertz of channel space and make that available for strictly low-power community broadcasting, which I would see as being done more as a registration process than formal licensing. That is, you find a frequency that is usable, fill out the paper forms, and notify the FCC that you have registered the use of that frequency. Then, follow the rules of the road in terms of interference, channel spacing and equipment and filtering and all that. As long as you follow the rules of the road, then there's no problem. That way it keeps it a much less formal way of dealing with it.

Globalizing from BelowJT: You've done work to bring microradio to other countries What are the policies and attitudes you've found from governments where you've tried to spread low-power radio? SD: It varies. In Haiti, it's fairly easy to do. The Lavalas Party, the peasants' party, is in power ostensibly in Haiti. A lot of people work with our people in the peasant movements. So, there's been no problems there. In fact, it's almost easier to do microradio in Haiti than it is here. In Mexico, it's very much opposed by the government. They have shut down stations. And, El Salvador does not recognize community radio as a service. They only recognize commercial and government radio. There's been ongoing fights in El Salvador over community radio. In some places no governments exist at all virtually. We supplied several transmitters to opposition forces in East Timor against Indonesia and they were eventually were able to move back into Dili (East Timor's capitol city) and one of our transmitters there was set up as an official People's Voice of Dili. JT: With the new FCC regulations going in place, talk about the strengths and weaknesses you see in what they've offered low-power people. Also, the NAB reaction and how this all leads into the mobilization this September for the counter-convention. SD: In my opinion, what the FCC has given us is massive damage control. Essentially, they were faced with an ungovernable situation with hundreds if not thousands of people going on the air in their communities with micropower stations. People are still doing it. They may have slowed down a bit. Some people anticipate they may get some sort of license. I think part of the reason the FCC did this is to break us up into two camps, those who are willing to go along with the process and those who see the process for what it is; tossing us a few crumbs while allowing the corporations to still dominate the airwaves, the people's resource. One, which in my opinion, has been stolen from the people. We're not the pirates. The corporations are the pirates here. We're not engaging in felonious activity. We are engaging in free speech activity. The strength of it is they are actually recognizing the validity of what we are saying. In fact, most of the things adopted by the FCC were recommendations given to them by the micropower movement as represented by the National Lawyers Guild on Democratic Communications. If you listen to the FCC, they're making statements that could come from our court documents and other public record statements over the period of time we've been doing this. They've come around, at least at the official level, of recognizing the necessity of this. Of course, this has sent the National Association of Broadcasters into a fit of apolexy. We've been in a state of war with the NAB for the last three or four years. They essentially declared war on us at one of their radio meetings. They put out orders to all their member stations, which is most every commercial station in this country, to locate and report any micropower station in their area regardless of whether that station was causing interference to any other existing services. Essentially, a search-and-destroy mission against micropower broadcasting. In response to the FCC's LP-FM ruling, the NAB got its bought-and-paid-for Congress critters to introduce their own legislation to roll back the few crumbs the FCC has given us. That bill has now passed the House and will come up for a vote in the Senate soon. So, what we are mobilizing for is a mass outpouring of people to come to the NAB's radio convention Who knows why they picked San Francisco. But, they're going to be right on our doorstep September 20-23 and we have every intention of confronting them and shutting down various aspects of their convention. Also, at the same time we will have our own counter-convention to push for independent, local, democratic media that will be the voice, the eyes and ears and the written hand of people in all these different communities across the country and the world. JT: A globalization from below. SD: Absolutely. My slogan is, "Act Globally, Revolt Locally."

Reaching OutJT: A question about the September mobilization. This weekend there was the first meeting of the Microradio Action Coalition. Given the origins of the microradio movement with Mbanna and others and the necessity of bringing microradio to all types of communities, do you see this mobilization reflecting the diversity of the groups that could make use of this kind of communication.? SD: Absolutely. That's our intent. You have to understand that when people of color do something illegal the repercussions for them are ten times as worse. We had one person in L.A., Michael Taylor, who met a very odd death over this issue. There was some weird, gnarly stuff going down. We don't know all the details. The point is when a person of color undertakes something like this for a community of people of color, they're gonna be subject to a lot more abuse. They could have the cops coming in and jacking them up on all kinds of pretexts. That's one of the deterring factors. There's not any issues, as far as I'm concerned, in this movement of racism and classism. The fact of life (is) if you are a person of color in this community, or any community, particularly if you are an activist and going up against the system, you could end up like Geronimo Pratt, 27 years behind the bars, because the FBI lied about what you did, or (like) Mumia or whoever. We definitely want to do a big outreach to youth of color to get them involved creating their own media so their own stories can be heard. So, we're going to do everything possible. We're basically here to help anybody, anytime set up a micropower station. If people want us to do workshops, or whatever, we'll do it. But when you have a situation where three youth of color standing on the sidewalk corner is considered a riot by cops and dealt with accordingly, then you have to put yourself in their shoes and understand why they have to be a little bit more circumspect about these sort of things in their communities. JT: What do you see for the future of community radio here in the US in the coming years? Do you see low-power taking the place of NPR-style public radio? SD: We should be so lucky. I think it (low-power FM) is going to have an ever-increasing place in communities. As long as people are forthright and militant enough about it to not give up their rights to the airwaves, then it's going to happen in a real major way. More people are looking at the issue of corporate control of every aspect of their lives. Communication is an absolutely essential part of being able to deal with this whole issue of corporate hegemony. Because if you can't communicate, you can't organize. If you can't organize, you can't fight back. And if you can't fight back, you have no hope of winning.

Symbiosis: Microradio and the NetJT:What kind of symbiosis do you see emerging between the Internet and low-power community radio? SD: It's a symbiosis that has actually been in process for some time. I would say a lot of it began in 1997 when we set up the A-Infos radio project site basically to exchange program content in digital file form on MP3. And since then what we're looking at is using the Web as an alternative distribution medium to share program materials. In Seattle, we had Studio X. "Voices of Occupied Seattle" was doing a live Internet feed from Seattle. That feed was picked up and rebroadcast by community and micropower stations around the world. We had calls, for example, from Amsterdam. Radio 100 was rebroadcasting the feed. What this does is allow us to both operate very locally as a grassroots community voice and at the same time operate globally as a grassroots global community to bring in breaking news, breaking things as they are happening right there in the immediacy of the event. Or, offer it on a delayed basis from taped material and content. So, bascially we are seeing this integrated relationship between the Net as a distribution medium, as a way of communicating between stations to organize ourselves more effectively, to share content, to set up, as needed, webcasting studios to provide content to other stations. In the Bay Area, we are going to be providing webcasting services of all major events that occur in the Bay area so stations around the world and people individually can tune in and listen or dial in or dial up. We see that there's going to be a very productive relationship between all these forms of grassroots media tool usage with the Internet, micropower broadcasting, inexpensive computer systems to edit your video and audio material and word processors to write your stories on. And using the Net to promulgate these on a global basis and using the micropower stations to promulgate it on a community basis. Not everyone in the community is gonna own a computer nor may they want to. Everyone's got a radio, though. JT:Last question. The Internet played a huge role in what happened in Seattle and people are continuing to use it as an effective tool. Do you think that the powers-that-be ever imagined it would work out this way? And, do you think there's any way they can reign it back in? SD: I'm sure they never conceived it would ever happen this way. But, that's the perversity of the Universe in which we live. Things take a life of their own. And at this point, I don't think they are going to be able to reign it back in. It has permeated everything too deeply to be uprooted. And if they do, it would cause such a major social upheaval. In terms of people, it would set off a major prairie fire of resistance. Back to Love and Rage in Seattle: The Day the WTO Stood Still |

On a warm, Saturday afternoon in late May, a motley crew of 35 or so

community radio activists from Berkeley, Oakland, San Francisco, Humboldt

County, Santa Cruz, Sacramento, Los Angeles, Austin, Pennsylvania, etc.

gathered in a Unitarian Church a couple of miles from where the original

Free Speech Movement was born in the fall of 1964. The meeting was long.

Seven hours. But, most people stuck it out. Their plans were ambitious, to

"bring Seattle to the airwaves" with a four-day counter-convention

featuring teach-ins, workshops, protests, street theatre and possibly

large-scale non-violent civil disobedience.

On a warm, Saturday afternoon in late May, a motley crew of 35 or so

community radio activists from Berkeley, Oakland, San Francisco, Humboldt

County, Santa Cruz, Sacramento, Los Angeles, Austin, Pennsylvania, etc.

gathered in a Unitarian Church a couple of miles from where the original

Free Speech Movement was born in the fall of 1964. The meeting was long.

Seven hours. But, most people stuck it out. Their plans were ambitious, to

"bring Seattle to the airwaves" with a four-day counter-convention

featuring teach-ins, workshops, protests, street theatre and possibly

large-scale non-violent civil disobedience.